By Dr. Colin Michie FRCPCH University of Central Lancashire

The International Music Council of UNESCO once declared that everyone has a right to silence. Sometimes, though, our ears violate this, creating their own diversity of noise. From a rasping fizz to a cicada-like buzzing, tinnitus troubles 10-15% of individuals in most populations.

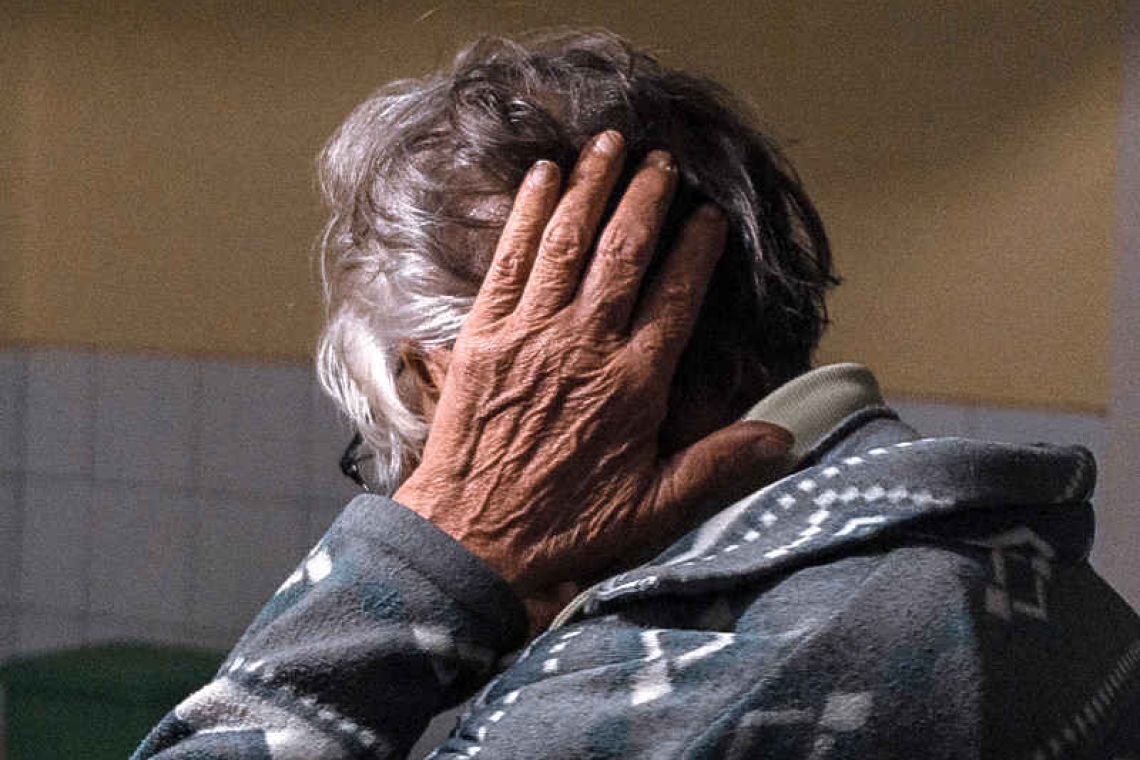

Coaches, gurus and lifestyle guides often recommend we listen to our bodies. However, flesh and bone can offer disturbing internal soundscapes. Movements of gas, wheezing, cracking from the neck, jaw, joints are not always calming. Most disturbing of all is tinnitus, a persistent din, perhaps zinging, or whistling, heard when there is no actual external sound. Sometimes, it is more obvious in one ear. To a sufferer, this can be torture, worse than any ear worm or deranged steam kettle; an irritating aural insult.

We all experience tinnitus for a brief time following a sudden loud din or crash. Curiously, we each have our own version of tinnitus – our personal whooshing, tinny or ghostly ear noises. These always exasperate or vex. They are never soothing, honeyed chords. Tinnitus can grow into an invisible, long-term disability. It can compromise attention, concentration, the quality of life, sleep, cognition, mental health. The condition differs between individuals. In some, it can vanish for no reason after several months of mayhem; it may become an intermittent pest. It is a condition that merits patience. Most sufferers probably do not seek medical help for it.

Tinnitus is more common in those over 65; it may be linked to ear wax, anatomical damage, inflammation or infection around the middle ear, the jaws, the neck, some medications. In some, it is accompanied by other disorders such as stress, anxiety or depression. If linked with significant hearing loss, tinnitus can contribute to social isolation over time. Some forms of tinnitus develop in those who have been exposed to noise, particularly in the workplace. Noise trauma can cause nerves in the inner ears to change their signalling patterns. The reduction of din in our living environments can be challenging, but needs consideration by all of us in order to protect our precious cochlea, preventing hearing loss and tinnitus.

Tinnitus results from incorrect or inappropriate signals sent through the brain by nerve cells that normally process information from the inner ears. This situation is helpfully termed a phantom perception. Some individuals with tinnitus have been found to have hyperactive nerves within several different areas of their brains, resembling the pattern seen in those suffering with chronic pain or phantom limb pain. Just as with these conditions, tinnitus probably has a number of different causes and many different ways of presenting. Perhaps this variety is a reflection of our very different personalities, processes of attention and coping mechanisms, which combine to direct how and what we perceive as sounds. We have no measurements for these different links, but they are likely to result in our brain networks interpreting or responding differently to signals from our ears. And let’s be honest – not all of us enjoy the same playlists. Similarly, we do not all experience the same grima or emotions from sounds, such as fingernails dragged across a blackboard!

Tinnitus needs investigation by a specialist, as should any disorder affecting our hearing. Although it is not an emergency, it is important to carefully review the situation for each sufferer. Hearing acuity requires careful checking for treatable problems. It may be useful to establish exactly what type of tinnitus is being experienced by an individual – and, if possible, its frequency or pitch.

Most attempts at treatments for tinnitus have failed. This condition attracts many unfounded claims for cures, particularly on the internet. This includes herbal treatments, various nutrients and acupuncture. There is no licensed curative pharmacological treatment. There are, however, considerable advantages to using coaching or counselling methods. There are likely to be significant benefits from cognitive behavioural therapy that change perceptions and abilities to live with this problem. The widespread use of cochlear implants to treat deafness from nerve damage coincidentally showed that the electrical stimulation from these devices reduces tinnitus in many recipients. This observation is being actively investigated as a hopeful lead – could electrical stimulation be a method to control the ability of our own ears to ring or hiss?

Specialist hearing units will apply stepwise approaches to managing their patients; they are likely to employ tinnitus matching to copy the tinnitus sound experienced by a patient, then play this sound, or something similar to it, back into their ears. This strategy directed at masking aberrant nerve messages may reduce the volume of tinnitus in some patients. These techniques too are being steadily refined. Tinnitus is a challenge for which reasonably effective treatments seem closer, thanks to growing knowledge of how to measure and manipulate brain functions.

Useful resources:

https://tinnitus.org.uk/support-for-you/

Dr. Colin Michie is currently the Associate Dean for Research and Knowledge Exchange at the School of Medicine in the University of Central Lancashire. He specializes in paediatrics, nutrition, and immunology. Michie has worked in the UK, southern Africa and Ghaza as a paediatrician and educator and was the associate Academic Dean for the American University of the Caribbean Medical School in Sint Maarten a few years ago.