The things you do; you do in a different way from I.

The things I do, I do in a different way from you.

––Errol Dunkley, Reggae artist, 1972

By Dr. Colin Michie FRCPCH University of Central Lancashire

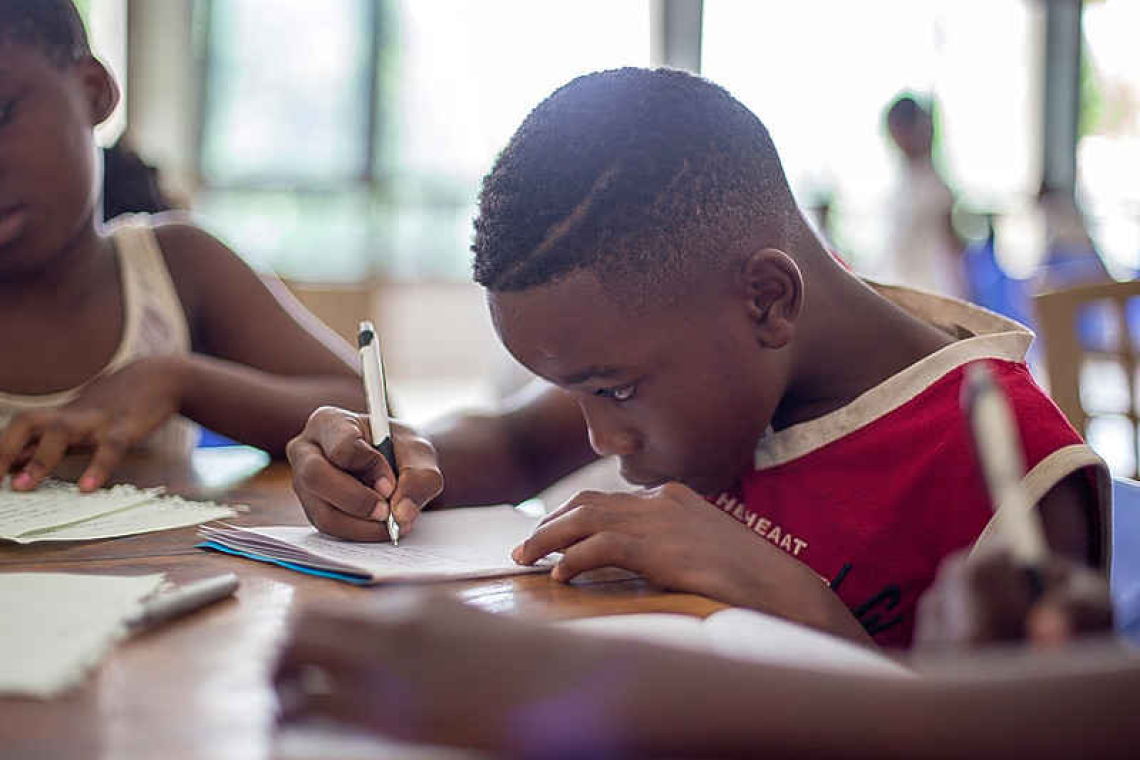

We are almost all schooled and encouraged to find a job. Schools and workplaces commonly direct us to be uniform, the same as the neighbours, the person at the next desk. But we differ in so many ways – in particular, how good we are at paying attention.

How focused are you? Are you easily distracted? Does your mind wander easily?

Attention to what is happening around us is considered by some to be a gift. It may be a source of considerable inspiration. In some, though, a lack of paying attention is accompanied by challenges of impulsive or disruptive behaviour together with hyperactivity – the condition of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. In the past, the problem was referred to as “Clumsy Child” syndrome; in the 1980s, it was known as “Attention Deficit Disorder” – the problems of school failure, anti-social behaviour and accidental injuries.

This condition has become increasingly recognised in children and adults over the last century, and treated with various medications since the 1960s. ADHD is more common in males; it may afflict 5-6% of children, and a lower proportion of adults. It is more frequent in those born prematurely, small, or with delays in their development. There may be a strong family history of ADHD. Recently, ADHD in adulthood has received growing recognition. Its severity or impact typically improves after adolescence, but can vary with time and may often not be considered as a diagnosis in adults.

The diagnosis of ADHD is made by a specialist doctor; blood tests or imaging are not required. International guidelines support this process, and the choices of treatments that should be offered. This process helps reduce stigma and cost. Regulated therapies improve school outcomes and reducing substance abuse, accidents, attempted suicide, social disruption and criminality.

Non-medical management from support groups is useful for all ages. Engagement of parents with teachers and schools helps interactions with and disciplines for hyperactive children. Anxiety is common in those with ADHD, troubling them and their parents. Differing cognitive behavioural approaches have been shown to be helpful in improving some aspects of ADHD in school. Meditation, yoga and sleep hygiene may help some, but have less-strong published evidence.

The value of music and music in gaming is being actively explored: music can help thinking and concentration. Attention may be modified too by diet, although impulsive activity is less responsive. Removing food colourings, attention to healthy foods and a good intake of omega-3 fatty acids may be beneficial in some. However, all investigations suggest that medications are more effective at improving attention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

Medications for ADHD include both stimulants (such as methylphenidate) or non-stimulants (clonidine, atomoxetine). As with all pharmaceuticals, these may have side-effects. For example, methylphenidate or Ritalin, used for this purpose since 1955, was named after Margarita for whom the drug was used to reduce her blood pressure. It can affect sleep and appetite and so different doses and routes of treatment may be recommended.

In 2020, over 15 million scripts were issued for this treatment in the US. Ritalin is commonly abused as a recreational drug – when misused in this way, it can become addictive; it is a powerful stimulant to the nervous system. The second most frequently prescribed medications are amphetamines – the most frequently used non-stimulant is probably atomoxetine. Regulations governing these medications vary considerably between countries.

For adults with ADHD, the complex process of driving a vehicle brings home challenges. Attention and controlled behaviours are crucial for road safety. A diagnosis of ADHD is usually reportable to regulatory agencies: they may permit those with a diagnosis of medically-controlled ADHD to drive.

Impacts of culture on the management of ADHD illustrate a difficulty facing diverse communities. We understand little of the causes of ADHD. Many clinical studies have been carried out, but in a relatively small number of countries and mostly with individuals of European descent. As we advance into this century, there is a growing need to improve the engagement of all in clinical studies.

Musicians since Dunkeley have created music about their ADHD, the stigmas associated with the condition and its treatment, the segregation they experienced in schools and communities. This is a medical condition that requires actions from all of us in improving our recognition of it, our support for researches into it, and our care if we know a family dealing with it. This will change community perspectives of ADHD on their islands, perhaps changing us too into more tolerant societies.

Useful resources:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014976342100049X?via%3Dihub

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/facts.html

https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/problems-disorders/adhd-in-adults

https://www.adhdfoundation.org.uk/

Dr. Colin Michie is currently the Associate Dean for Research and Knowledge Exchange at the School of Medicine in the University of Central Lancashire. He specializes in paediatrics, nutrition, and immunology. Michie has worked in the UK, southern Africa and Ghaza as a paediatrician and educator and was the associate Academic Dean for the American University of the Caribbean Medical School in Sint Maarten a few years ago.